The Hammer on the Church Door: Luther’s 95 Theses and the Unintended Reformation

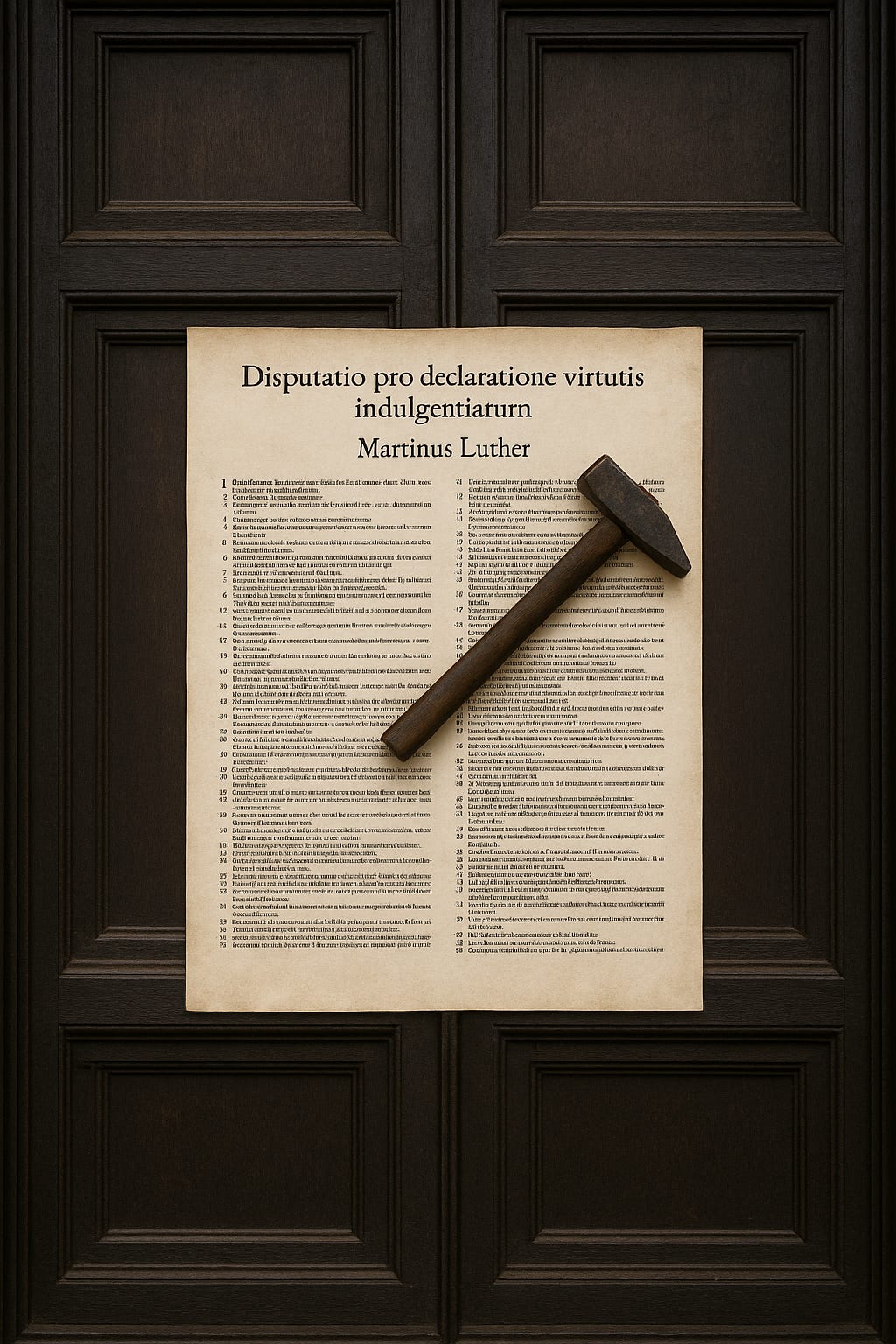

On October 31, 1517, a little-known German monk named Martin Luther nailed a list of 95 propositions to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. These “theses”—questions and challenges for academic debate—were written in Latin, intended for clerical eyes, and focused narrowly on the abuse of indulgences. What Luther could not have imagined was that this small act of protest would become a spark that lit a conflagration, reshaping the Western Church, dividing Christendom, and setting the stage for the modern world.

Luther’s 95 Theses were born from a crisis of conscience. As an Augustinian friar and professor of theology, Luther had long wrestled with the question of how sinful man could be made right before a holy God. The Church of his day pointed to penance, confession, and the treasury of merit dispensed through indulgences—essentially a remission of the temporal punishment due to sin. These indulgences, once limited in scope, had become commercialized and widely abused. Agents like Johann Tetzel famously promised salvation itself in exchange for coin: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs."

Luther’s protest was, at least initially, not a rejection of the papacy, sacraments, or Church authority. It was a call to reform what he saw as theologically indefensible practices. Among the theses, Luther questioned whether the pope had the power to forgive sins for money (#5, #6), whether indulgences could truly save (#21), and whether true repentance was even possible through such means (#1). His first thesis sets the tone: “When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ‘Repent,’ he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.”

This was not merely a critique of indulgences—it was a reassertion of the Gospel itself. Luther’s academic protest quickly escaped the bounds of university debate. Translated into German and printed on Gutenberg’s newly widespread press, the Theses found an eager audience among a laity weary of clerical excess and spiritual confusion. Within months, Luther became the unwitting voice of a growing movement. Within years, he would be excommunicated.

It is important to understand that Luther did not begin by seeking to divide the Church. Like many reformers before him—men such as Jan Hus and John Wycliffe—he sought to correct error from within. But the institution, fattened on centuries of wealth and power, responded not with humility but with condemnation. By 1521, at the Diet of Worms, Luther would stand before the Holy Roman Emperor and declare, “Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason... my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant.” Thus, a monk who once prayed for guidance in a thunderstorm became the reluctant architect of a religious revolution.

The 95 Theses, while relatively tame by modern standards, opened a wound that had long been festering. They touched a nerve that ran deep: the need for a Church rooted in truth, not tradition alone; in the authority of Scripture, not merely the declarations of Rome. The Reformation that followed would be marked by schism, bloodshed, and theological conflict. But it would also bring a renewed emphasis on biblical literacy, the priesthood of all believers, and salvation by grace through faith.

Anglicans often find themselves in a unique position in relation to Luther. We are not Lutherans, yet we share his love for Scripture, his reverence for grace, and his passion for reform. The English Reformation, while distinct in origin, was shaped by the same winds that blew through Wittenberg. Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer echoes Luther’s pastoral heart in many ways: accessible worship, biblical preaching, and a deep concern for the salvation of souls.

Yet we must also remember that reformation without charity becomes rebellion. Luther’s movement fractured into myriad sects, many of which quickly splintered over increasingly obscure points of doctrine. What began as a call for repentance became, in some circles, a rejection of tradition altogether. The Anglican way—reformed yet catholic—seeks to retain the wisdom of the early Church even while acknowledging the necessary reforms brought to light by men like Luther.

Five hundred years on, the hammer still echoes. Luther’s 95 Theses remind us that the Church must always be subject to the Word of God. Tradition is valuable, but it must be weighed against Scripture. Authority is necessary, but it must serve truth. The moment the Church forgets this, it drifts toward indulgence—whether of money, of pride, or of power.

Let us be grateful, then, not only for Luther’s courage, but also for the uncomfortable question his hammer still asks of us: Are we a Church that repents? Or one that simply reforms its image?

May God grant us the grace to pursue holiness in truth and humility, that the Church might once again be “always reforming”—but only according to the Word of God.