The First Protestant Hymnal: A Reformation of Song (1524)

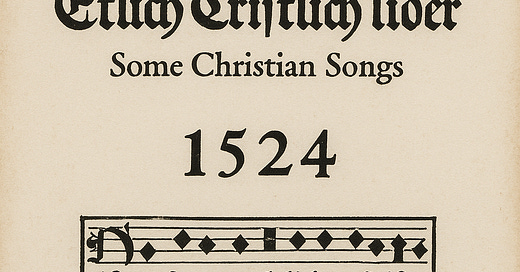

In the early thunder of the Protestant Reformation, long before pulpits were filled with evangelical fire or printing presses thundered out tracts by the thousands, a quieter—but equally revolutionary—movement began to stir among the people: the return of sacred song to the congregation. The year was 1524, and in Wittenberg, Germany, a modest little book changed the face of Christian worship forever. That book was Etlich Cristlich lider—Some Christian Songs—the very first Protestant hymnal.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of this moment. For centuries, the Church had reserved sung worship largely for choirs and clerics. The liturgy was sung in Latin, unintelligible to most parishioners, and while beautiful, it was often alienating. But Martin Luther, the Augustinian monk turned reformer, believed something radical: that worship belonged to the people—and that singing was one of the most powerful means of theological formation and spiritual unity.

Luther understood the pedagogical and spiritual power of music. “Next to the Word of God,” he wrote, “the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world.” Thus, in collaboration with composer Johann Walter and printers such as Joseph Klug, Luther helped produce Etlich Cristlich lider, a collection of just eight hymns—four penned or translated by Luther himself—all in German.

Among them was the powerful “Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein” (Dear Christians, One and All, Rejoice), a poetic testimony of salvation by grace. Unlike the distant plainsong of the medieval Church, these hymns were designed for congregational singing—a bold declaration that ordinary men and women could not only hear the Gospel, but sing it.

The hymnal was printed in Wittenberg by Klug and, depending on the edition, possibly by Andreas Rhau in Nuremberg as well. The book’s influence spread rapidly across German-speaking lands and beyond. It inspired other collections, expanding Lutheran hymnody and eventually influencing Reformed, Anglican, and even modern evangelical traditions.

Indeed, for Anglicans, the theological and liturgical implications are familiar. The 1549 Book of Common Prayer would later invite English worshippers into a similarly participatory model—reclaiming the vernacular and giving sacred expression to the voice of the people. Hymnals, eventually integrated into Anglican worship, owe much to the 1524 German example.

But the Protestant hymnal was not merely about accessibility. It was a declaration: that doctrine could be sung, that worship could be personal, and that the Church could be reformed not only by preaching and printing, but by praise.

The legacy of Etlich Cristlich lider endures. Every time a congregation stands to sing, whether with the poetic meter of Watts or the simple chorus of modern worship, they participate in a tradition launched by that small, revolutionary book printed in Wittenberg. It reminds us that the Reformation was not only a battle for truth, but a reawakening of joy.

Let the Church remember: in 1524, the people began to sing again.